Research tells us that poverty and reading levels are closely connected. Nationally, 1st graders from low-income families have 50% smaller vocabularies than their peers from higher income families. Before they even enter school, children living in poverty face a host of challenges that their wealthier peers do not: food and housing insecurity, poor health care and unsafe environments, limited exposure to books and language. Any one of these obstacles can affect their school performance, cognitive development, and ability to learn; some children face all of them, all at once. Over 60% of low-income families have no children’s books in the home. Just like their wealthier peers, poor children need books that they like, ones they choose themselves, at their level and on topics that interest them.

It’s often assumed that families without books lack interest in reading. But that is not necessarily the case. “When poor people, even those at low literacy levels, have a little extra money, they will buy inexpensive books,” explains Susan B. Neuman, a professor at the University of Michigan, who specializes in early literacy development and co-authored the study in Philadelphia. “But some families have so little disposable income, they can’t afford any books.” This is bad news for their kids. Around the world, one thing that has been shown to be a consistently powerful predictor of academic achievement is a home library. [1]

Title 1 is the nation’s oldest and largest federally funded program, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Annually, it provides over $16 billion dollars to school systems across the country for students at risk of failure and living at or near poverty. The purpose of Title 1 funding, “is to ensure that all children have a fair, equal, and significant opportunity to obtain a high quality education and reach, at minimum, proficiency on challenging state academic achievement standards and state academic assessments.”

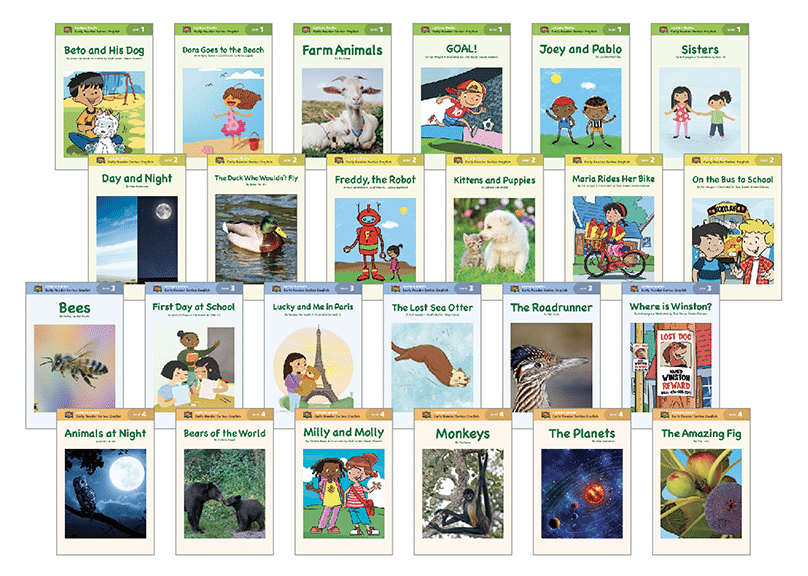

Many Title I schools are in low-income neighborhoods and often lack county or public libraries and other services to support literacy and reading development. And poor families may not have the income to purchase books like middle class or wealthy class families might have.

The Latino Family Literacy Project can train teachers who work with parents at school to teach parents to read with their children and kids can practice their English skills. It’s a win-win. Lectura Books is a fantastic resource to create lending libraries in schools.

[1] A study of close to 3,000 children in Germany found that the number of books in the home strongly predicted reading achievement — even after controlling for the parents’ education levels and income. And a massive, longitudinal study examining the educational attainment of 70,000 students from 27 countries found, surprisingly, that having lots of books in the home was as good a predictor of children’s educational attainment as parents’ education levels. In fact, access to books was more predictive than the father’s occupation or the family’s standard of living. The greatest impact of book access was seen among the least educated and poorest families.